In a recent op-ed in the Lansing State Journal, Citizens Utility Board (CUB) of Michigan Executive Director Amy Bandyk writes that it is “the utilities themselves,” rather than other alleged culprits like rooftop solar customers, that “have made our electricity more expensive and unreliable by failing to invest in the distribution system wisely.” What exactly do we mean by “wise” investments into the electric grid?

New testimony filed on behalf of CUB and other groups in Consumers Energy’s electric rate case strikes at the heart of why Michigan has such a problem with electric reliability, and what to do about it.

Consumers Energy’s track record building and maintaining the grid of poles and wires that keep the lights on shows the utility puts too many resources into expensive rebuilds of grid infrastructure, even if there are much cheaper alternatives that could just as effectively maintain reliability, and not enough into detecting and anticipating reliability problems that lead to mass power outages.

Imagine if every time you needed to fix something with your car—a dented bumper, a new tire—instead of paying hundreds of dollars to fix the issue, you just bought a new car for thousands of dollars.

You might, however, buy a new car every few months if you could get someone else to pay for it. In the case of electric utilities, that “someone else” is the ratepayer. Under the cost-of-service utility regulatory model that Michigan and many other states use, utilities can sometimes have a perverse incentive to overspend on capital because they can charge ratepayers for those capital investments later. The bill charges include not only the cost of the capital itself but also a return for the utility’s shareholders.

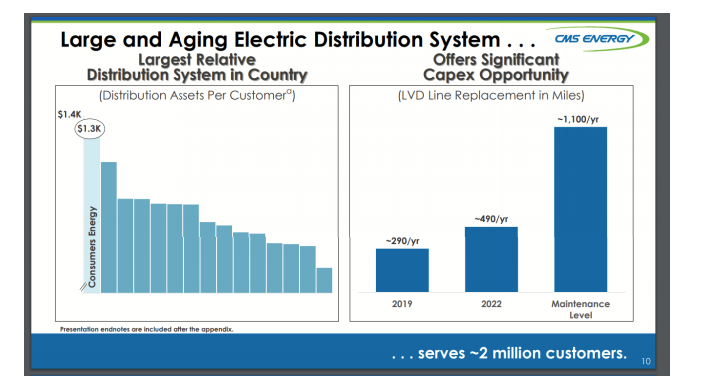

The perverse incentive is on display in a slide Consumers Energy parent company CMS Energy presented at a recent investor meeting (shown above). The slide touted the “large and aging electric distribution system” as a “significant capex opportunity” for investors. The system is the most expensive in the country in terms of the dollar value of the distribution assets per customer. That means there is lots of infrastructure that when replaced generates a return for the utility shareholders on the capital deployed. In particular, the slide pointed to the money making opportunity for investors represented by an “unprecedented 70% increase in annual LVD [low-voltage distribution] line replacements” from 2019 to 2022 as proposed by the utility, as expert witness Robert Ozar, a senior consultant at 5 Lakes Energy who worked at the Michigan Public Service Commission for 40 years, wrote in the testimony.

“It is bad enough that the Company’s electric distribution system is the costliest of comparable utilities in the country. That ratepayers, in particular residential customers, many of whom struggle to pay their electric bills, must bear the cost of extensive LVD line replacements is not an ‘opportunity’ but a ‘burden,” Ozar said.

Consumers Energy could make its distribution system less expensive, Ozar suggests, by taking steps to better monitor the grid so infrastructure can be maintained to prolong its life before it must be replaced. But there is an “absence of any continuous asset condition monitoring of the Company’s HVD or LVD lines,” he said.

The utility does check line conditions regularly, using methods like helicopter inspections and biannual ground patrols. But “regularly” is not the same as “continuously” because it leaves plenty of time for things to fail unexpectedly. “However, because the Company’s distribution system monitoring occurs on a scheduled basis, with significant time periods in between asset evaluations, it has an obvious inherent limitation,” Ozar said. “It is incapable of flagging incipient adverse conditions that occur in the interim between the scheduled monitoring. Decreasing the timespan between scheduled monitoring, under this paradigm, could improve asset evaluation but cannot eliminate this limitation.”

It just happens that there is a technology that can detect “incipient adverse conditions” in the grid. Distribution Fault Anticipation Technology (DFA) was developed by Texas A&M University researchers and the Electric Power Research Institute. It consists of software connected to distribution circuits that collects data from the electric signals and analyzes that data to detect “signatures” consistent with potential equipment failure.

Typically, outside of routine inspections, the utility is not going to know there is a problem brewing until the power goes out or some member of the public calls the utility to notify them of an impending issue, like a tree branch touching a line. But this DFA technology can actually automatically detect and locate these routine problems. The technology “not only has the potential to identify a fault before an outage event occurs, but it has the potential to identify ‘upstream’ conditions that may cause ‘downstream’ events,” Ozar said. “As a result, where traditional corrective action may address the manifest cause of an event (e.g., broken conductor), DFA technology has the ability to detect underlying conditions and provide proactive repairs.” Ozar recommends that Consumers Energy should explore DFA technology and propose ways to start integrating it into their systems.

In addition, to keep the utilities focused on spending ratepayer dollars wisely, Ozar calls for performance-based ratemaking, in which the utility incentives would be linked to cost-effective improvements in electric service, rather than the status quo, in which the utility is driven by returns to shareholders. Performance-based ratemaking is something CUB has strongly supported—read our 2020 report on measures to improve reliability in Michigan for more on this topic.

Dollars for the distribution system are scarce. Ratepayer pockets are not inexhaustible. So there is responsibility on the part of the utility to to spend ratepayers’ money effectively.