The Upper Peninsula (UP) Energy Task Force, formed in June by an order from Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, has spent its first few meetings studying the lay of the land of the Upper Peninsula. Now, the Task Force is in its very early stages of determining the potential paths forward for the UP’s energy problems.

The goal is to help the region deal with all types of interruptions to the energy system. In particular, the task force is tackling the region’s heavy reliance on propane gas for heating and limited routes for fuel supply, such as Enbridge’s Line 5 pipeline, the safety of which the governor and Attorney General Dana Nessel are currently challenging.

The group will issue two reports: one on propane by March 31, 2020 and a final report a year later with a focus on “security, reliability, affordability and environmental soundness.”

On Sept. 20, 2019 at Finlandia University in Hancock, the task force heard from representatives of the providers of much of the energy that keep the peninsula warm in its harsh winters:

- Plains Midstream Canada, which processes a variety of natural gas liquids (NGLs), including propane, and delivers and stores these products,

- Enbridge, which operates the pipelines that carry natural gas liquids and crude oil, and

- SEMCO, a major natural gas utility in Michigan that distributes gas to customers.

The presentations from the meeting can be viewed here. The final hour of the meeting was for public comment. More than thirty people from the local area shared concerns and asked questions. The Task Force will respond to these comments in its reports.

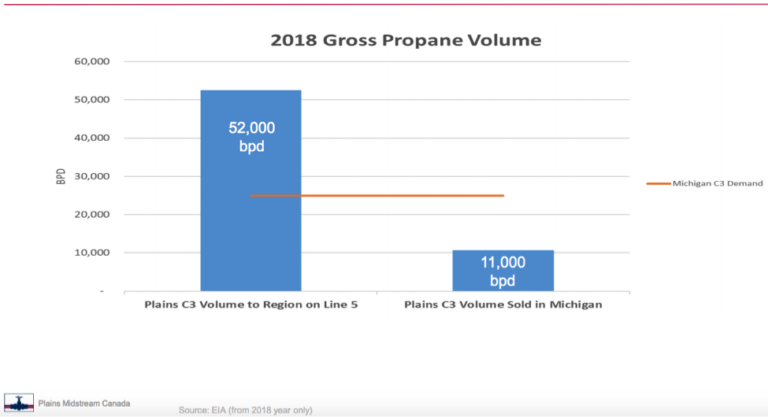

The message conveyed to the task force, according to task force member and Marquette City Commission member Jenn Hill (also the secretary of the board of directors for the Citizens Utility Board of Michigan), is that not just the UP, but Michigan is a relatively small offramp for propane and natural gas as it makes its way toward other markets. Recently those markets are increasingly located overseas, primarily in Asia, since North America is now the cheapest source of natural gas. Of about 52,000 barrels per day of propane that Plains Midstream produces by fractionating natural gas liquids from the Line 5 pipeline, only about 11,000 is sold in Michigan.

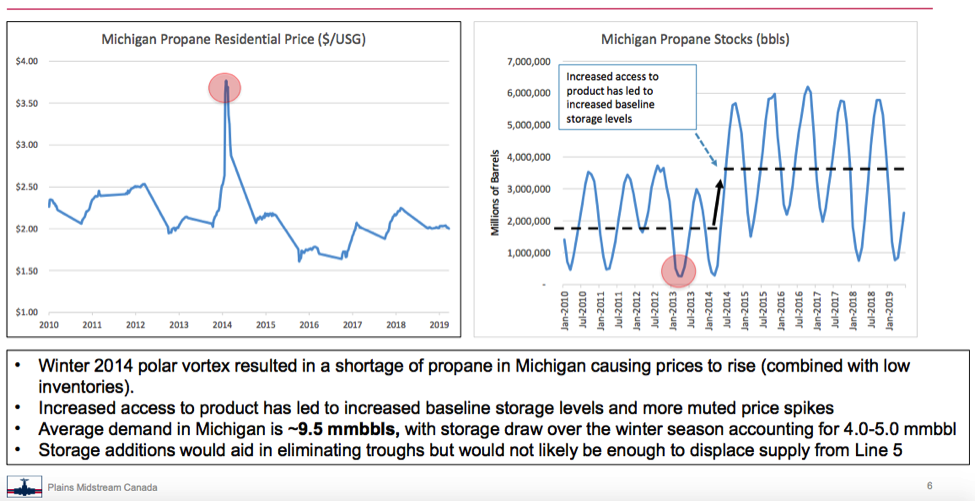

In the UP, 25% of residences rely on propane as a primary energy source. Since there are few alternatives to natural gas (and propane, derived from natural gas) for heating, “it makes it really easy for our prices to go up,” Hill said. In the winter of 2013-14, pipeline closures due to routine maintenance and unexpected extreme weather, plus high demand for propane for crop drying and heating use spurred by the polar vortex, caused residential propane prices to jump nearly 90%.

The group learned that Enbridge’s prices to move the product are capped by federal regulators, no matter the level of demand, leaving questions about who profited from these price spikes. Another question raised is why residential customers in Wisconsin and Minnesota consistently pay lower prices for propane than residential customers in Michigan.

The meeting also emphasized the tight, steady state nature of the system. In summary, by controlling the pressure in the Line 5 pipeline, product is sent in batches of 80% light crude and 20% NGLs as customers make contracts to buy it. Delivery through a pipeline is more efficient than by railroad. Contracts can be negotiated for just-in-time delivery using a pipeline, in contrast to using trains, which require a 10-day delivery window. Plains Marketing estimated that the cost through a pipeline is pennies per gallon while through rail is dimes per gallon.

Both Plains Marketing and Enbridge noted that as demand has increased for the product, they did not want to slow down its movement through the pipeline. To meet the rising demand, Plains Marketing and other companies expanded long-term storage in southeast Michigan and in Sarnia, Ontario. This storage is mostly in enormous underground salt caverns unique to the geology of the area. They are relatively inexpensive to build and can be used to store NGLs for months at a time. These storage facilities are important for the Midwest US and Eastern North American propane supply and to supply the worldwide market.

To complete its understanding of the current propane delivery system, the Task Force has spent part of its August and September meetings learning about the operations of the facility in Rapid River in the UP, which supplies most of the propane used by customers in the UP, as well as some in Wisconsin. The Rapid River facility is owned by Plains Marketing and receives inputs only from Line 5. It is managed to meet seasonal demands, is used primarily in the wintertime and has storage that would serve approximately two weeks and cannot be relied on for longer than that. The distribution companies load propane onto trucks at the facility and deliver it to customers as needed.

Natural gas also has very specific delivery mechanisms to the region. In its presentation, SEMCO explained how there are two pipelines that bring natural gas to the UP and that they are separate from the NGL/crude oil system. These two pipelines are being joined for the first time in 2019, with construction of a connector in Marquette County. Customers pay to install the equipment to join their homes and other buildings to this system.

Hill compared the situation to the big trend in the electric sector over the past several years, in which regulators, consumer groups and others are pushing utilities away from rigid assets like centralized fossil-fuel burning plants to flexible, distributed assets like rooftop solar. Fossil-fuel power plants are multi-million dollar investments and require a large amount of poles, wires and maintenance and imported fuel to serve customers, as opposed to distributed generation where the electricity is generated closer to where it is used by the customer and the customer even has the option to install their own solar panels and batteries to meet their energy needs. Currently the UP system for delivering heating sources is much more similar to the former model than the latter.

So how can the UP become more flexible and resilient? One idea suggested by Task Force member Douglas Jester of 5 Lakes Energy is to increase the amount of propane storage on site for customers. For example, a standard 500-gallon tank could be replaced with a 1,000-gallon tank. That extra capacity would give UP customers more flexibility to weather periods of propane price volatility. Michigan Public Service Commissioner Dan Scripps suggested that the task force consider several possible scenarios: a temporary disruption that happens immediately or over the next three years, or a permanent disruption that happens immediately or over the next three years.

UP Task Force’s next meeting is in Sault Ste. Marie at Lake Superior State University on Oct. 1. The group will continue to seek public comment and learn about energy assistance and consumer protection programs.