For decades, many states have required their energy utilities to regularly submit long-term plans laying out what the utilities believe is the best way to provide reliable and cost-effective service to their customers. Known as “integrated resource plans” or IRPs, this planning process forces the utility to show what investments and strategies it will make – what type of power plants to build, what older plants to retire, what kind of energy efficiency to pursue – depending on a variety of scenarios, from commodity price fluctuations to different types of government regulation that may or may not be implemented.

In short, the IRP not only gives customers an idea of what their utility will do for them, it also, like a math test, makes utilities “show their work” so the public can evaluate whether what they are proposing makes sense, and if necessary make the case for a better way.

But up until not even three years ago, Michigan had only an informal IRP process and did not explicitly mandate IRPs by law. A late 2016 bill passed by the state legislature required utilities to submit IRPs, and a year later the Michigan Public Service Commission (MPSC) established deadlines for these plans.

Michigan ratepayers are now seeing why every detail of how their utilities plan for the future needs to be scrutinized. A number of stakeholders participating in DTE Energy’s IRP approval process have identified major flaws in DTE’s plan that, if not corrected, could lead to the utility saddling its ratepayers with avoidable costs.

DTE, the largest electric utility in Michigan, filed its IRP on March 29. It is meant to represent what DTE thinks is its “most reasonable and prudent means of meeting the electric utility’s capacity and needs” for the next 5, 10 and 15 years.

But the plan is anything but reasonable or prudent, according to testimony filed in August by a number of groups representing diverse interests, ranging from environmental groups to business groups concerned about the price of their power to the office of the Michigan Attorney General.

As the testimony reveals, again and again, DTE’s IRP makes choices that would lead to higher costs passed onto its customers.

Delving into DTE’s IRP can quickly get into the weeds of complicated economic modeling, but let’s discuss in simple terms a few examples of the problems with the IRP and the impact on customers that would result from what DTE is proposing.

First, DTE assumed it would have to keep continuously running a number of coal-fired plants that have been around for decades, some going back to the 1960s and late 1950s, even though those plants may be for much of the year losing money by staying open. This is detailed in testimony from Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) Senior Energy Analyst Joseph Daniel (check out his highly informative and highly entertaining Twitter feed as well as his blog post on the IRP for more) filed on behalf of the Environmental Law & Policy Center, the Ecology Center, the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA), UCS and Vote Solar.

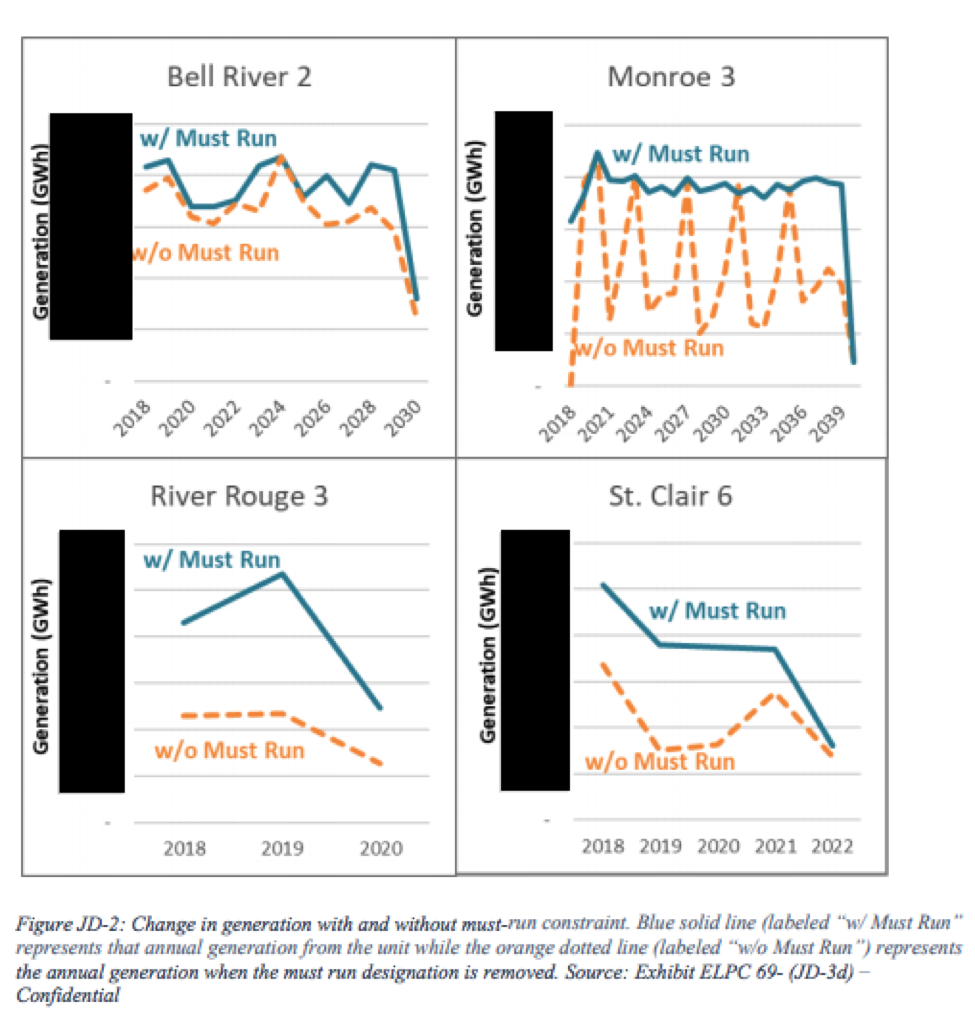

Daniel gives several recent examples of utilities around the country having found that it is cheaper to only run their aging coal plants seasonally (such as in the summer months when the heat makes electricity demand particularly high). But DTE’s modeling made it impossible for the utility to even discover if those kinds of seasonal strategies can benefit customers because it designated these coal plants in question as “must-run” resources that have to be available, regardless of economics.

While redacted are exact numbers about how much less DTE would have to spend on things like fuel, personnel and maintenance if it did not require these coal plants to be run in its modeling, Daniel’s charts in the report do show a significant drop-off in amount of operation when the “must-run” designation is removed (see image below).

“The Company’s modeling represents a future that is over-reliant on unnecessarily expensive resources and does not represent the most reasonable and prudent means of meeting the electric utility’s energy need,” Daniel testified.

Next, take energy efficiency. Being more efficient with energy and using less of it is typically cheaper than generating that same energy through a power plant. Efficiency and reducing energy waste, if done at scale, saves all ratepayers money on their utility bill by negating the need to build new generation or to run expensive peaker plants during high demand times.

DTE is required by the MPSC to reduce a certain amount of energy waste, and as part of the IRP it must analyze the costs and benefits of doing more energy efficiency programs (such as through rebates to customers for more efficient appliances).

But as consultant Chris Neme argues in testimony filed on behalf of the Michigan Environmental Council, the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) and the Sierra Club, the IRP’s analysis of energy efficiency as an option is unreasonably slanted toward the costs of energy efficiency, while underappreciating the benefits. DTE assumed that marketing and administrative costs of rebate programs would increase proportionate to increases in the amount of rebates, which doesn’t make sense. (Full disclosure: Michigan Environmental Council Energy Policy & Legislative Affairs Director Charlotte Jameson is a board member of CUB.)

The utility’s unrealistic assumptions lead to the IRP favoring a goal of reducing energy waste by 1.5% per year, while Neme found that 2% is more advantageous for customers once the assumptions are corrected.

Half a percentage point is a lot of energy use when we are talking about a utility that serves 2.2 million customers. Essentially, under DTE’s plan, customers would both be paying for more energy to be generated by power plants (because that energy would not be saved) and would get fewer incentives like rebates with which to make their homes more efficient and cut their electric bills.

Energy efficiency is particularly important for low and moderate-income consumers. Lower-income households spend a higher percentage of their budgets on energy compared to higher-income households, so every kilowatt-hour of electricity saved is particularly precious for poorer households. As Daniel points out in his testimony, the average family in Michigan living below the federal poverty line spends 17% of their annual income on electricity, compared to 3% for the average family living above the federal poverty line.

The point is: undercutting energy efficiency in long-range planning is especially painful for the ratepayers among us who already face the toughest economic burden.

The IRP also underestimates how much energy can be produced by solar power and overinflates expectations for the costs of solar. SEIA Director of Rate Design Kevin Lucas corrected the biases against solar and reran the economic models in the IRP. The result was a more solar-heavy resource plan that saves DTE customer’s about $1 billion compared to DTE’s IRP.

There are numerous other failings in the IRP, such as a decision to not pursue competitive bids for power projects that could be cheaper for customers than DTE’s preferred option of using its own power plants (which gives the company and its shareholders an extra return compared to buying power from outside entities). Consult the testimony of 5 Lakes Energy Partner (and CUB advisor) Douglas Jester to learn more.

Ignoring competitive bids narrows the scope of DTE’s IRP when it should be considering all options. “This is supposed to be the place where modeling is done, where optimization is done, where you’re supposed to explore all options for prudently providing power to your customers,” NRDC Senior Energy Policy Analyst Ariana Gonzalez said in an article by Utility Dive. “And to not look at third party is not fulfilling that requirement.”

It is fortunate that the Michigan legislature chose to follow other states and require a formal IRP process. By submitting this plan, DTE had to show its work on the important question of how to plan for its customers’ futures. So far, DTE is getting a failing grade.

But the IRP can and will likely be revised. The case at the MPSC is U-20471. Go to the MPSC website and comment on the case to help make the revised IRP better.